The foodies are back, but where are the workers?

Summer has begun, and the demand for the consumption of “experiences” is back (just like that), but the supply chain of human workers will take a long time to catch up as the U.S. economy reopens.

Like the tens of millions of Americans who traveled on Memorial Day weekend (by plane or by car), I spent the week at the beach in the Outer Banks (OBX) of North Carolina, and it really seemed like the first week that things were “back to normal” with tourist volume—corresponding with many visitors having been fully vaccinated and Covid restrictions fully lifted (in NC, as of mid-May). It was great to be able to eat out at restaurants again, but it wasn’t so easy to get a table. Once seated, I immediately noticed how short-staffed these restaurants were. It seems quite clear that leisure/hospitality businesses are having trouble getting back to full speed—keeping up with the surging demand for the “experiences” they sell—because they just can’t find enough workers.

I did some “organic research” while on vacation, talking with the bartenders, wait staff and small retail business owners. I learned that these OBX businesses were having trouble hiring staff, because most of their prior workers had moved out of the area. In addition, a significant share of their summer season workers would typically come from abroad on international exchange visas, which were shut down at the start of the pandemic and have yet to be restarted (probably justifiably, given that much of the rest of the world is lagging the U.S. in vaccination progress). This was a “supply chain bottleneck” completely focused on the labor input—people!

I also did a lot of Google searching that week in the OBX for “restaurants near me” and then trying to secure a reservation. It got me thinking how everyone else around me was probably doing the same thing. We were all generating real-time data on the demand for restaurants in the area. And I also realized that probably, almost exactly no one in the OBX that week was googling “jobs near me.” So, Google searches could give us a real-time, local-level indicator of the excess demand for restaurant consumption vs. the supply of potential workers to work there.

When I got home, I dug in. What can Google searches for “restaurants near me” compared to searches for “jobs near me” in the U.S. over the past year tell us?

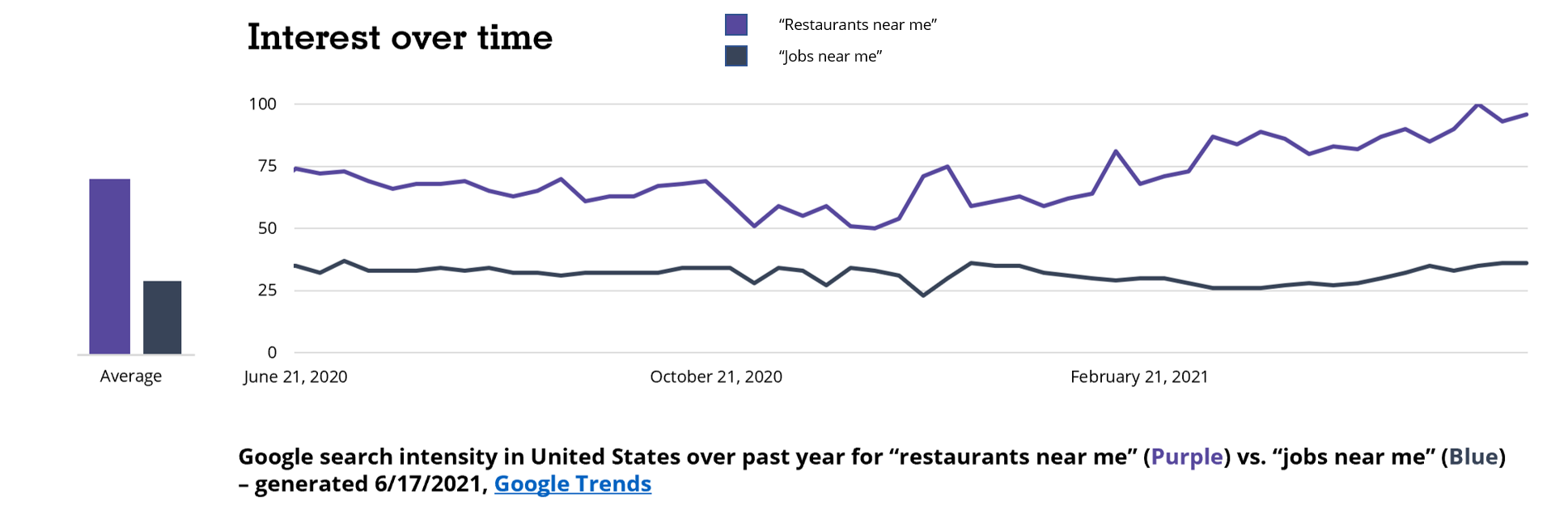

Figure 1. Google search intensity in United States over past year for “restaurants near me” (Purple) vs. “jobs near me” (Blue) – generated 6/17/2021, Google Trends

Sure enough, we can see that nationwide, searching to find places to go out to eat started to outpace searching for work, just as vaccination rates started ramping up this spring.

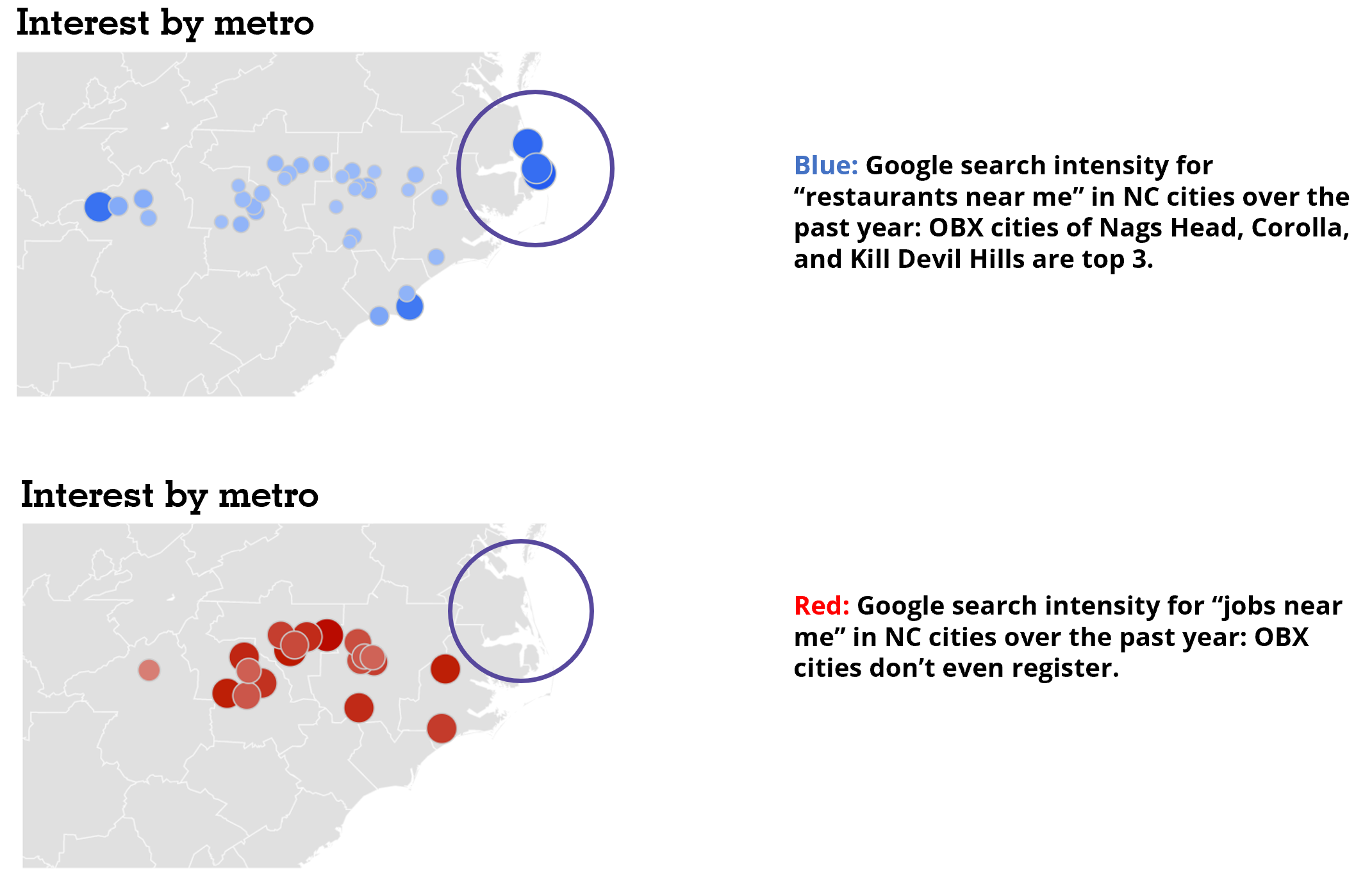

I then drilled down geographically to “see” the place I had just visited, the OBX, a place where most people are there for vacation and not for “ordinary life”—unless their economic livelihood revolves around a leisure/hospitality business. (You see, there’s not much to do in the OBX except be on vacation.)

Figure 2. Maps pulled from Google Trends on 6/17/21:

The lack of searches for “jobs near me” (yes, any kind of “jobs near me”) in the OBX is a strong indicator that the pool of potential leisure/hospitality workers already located in the OBX is extremely limited. Demand for restaurants is extremely high, and the supply of workers for those restaurants is virtually nonexistent. Is what’s happening in the OBX indicative of what’s happening in other parts of the country right now, or is it an outlier?

Thanks to a collaboration with Avison Young’s Director of Data Science, Brian Harper, the two of us analyzed Google Trends data on these two search terms for different localities around the country to look at where restaurant searches had surged and how well labor supply (represented by job searches) had kept up. We chose to look at popular tourist towns as well as large cities, and where there was not enough density to see the search intensities in a particular town (like Corolla, NC, where I was on vacation) we included the next closest place (like the Virginia Beach area, or the entire state of NC).

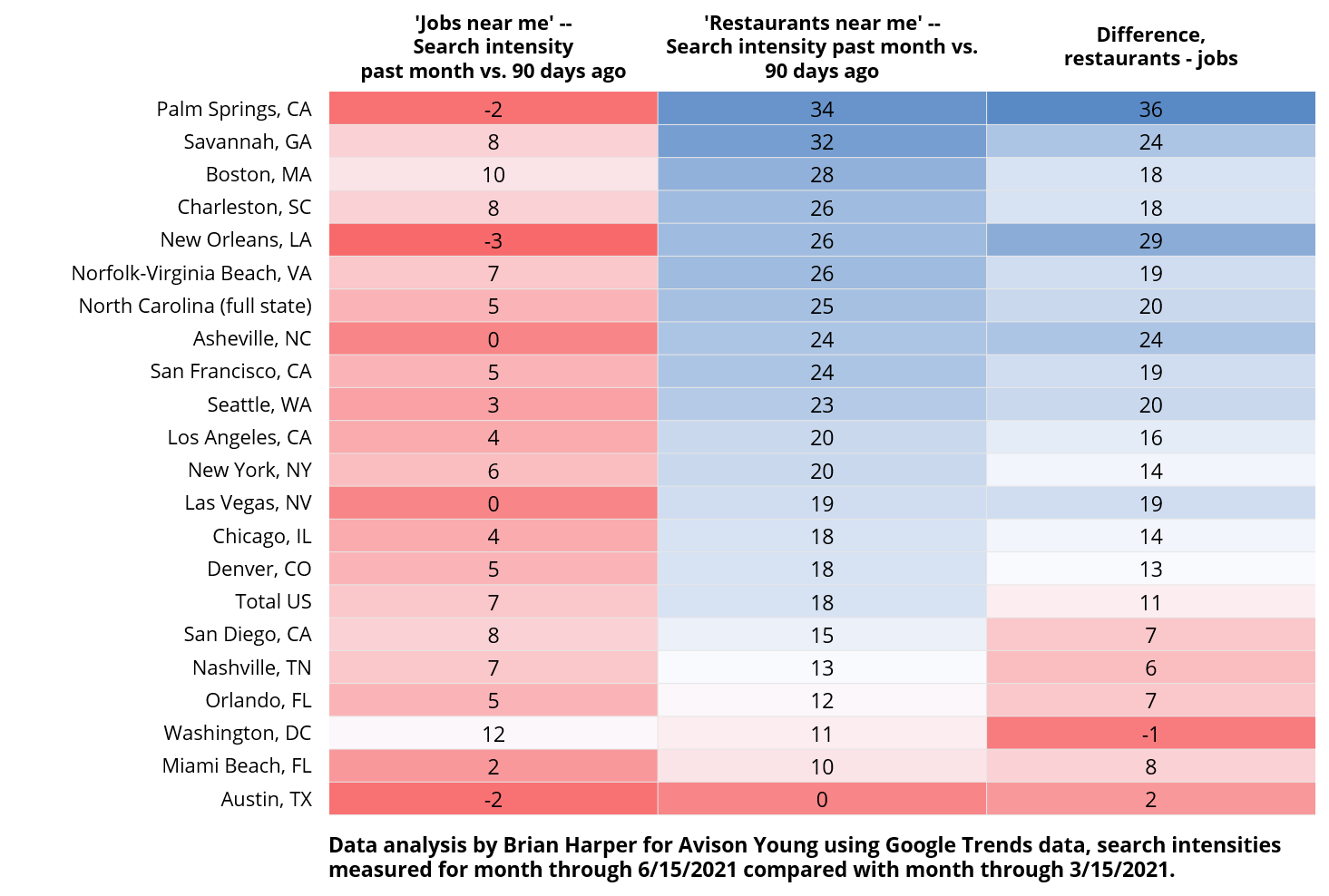

We then constructed a Google Trends-version of an indicator of the “excess demand” for (or “shortage” of) restaurant workers, based on the difference between the 90-day trend in search intensities for “restaurants near me” and the 90-day trend in searches for “jobs near me.” (The 90-day interval, going back to mid-March, picks up the surge in demand corresponding to vaccination rates and the lifting of state-level business restrictions, with Google search intensities measured over the past month.)

Figure 3. A real-time indicator of labor shortages in the restaurant industry: Google searches for “restaurants near me” far outpacing those for “jobs near me” since mid-March:

The table shows that the excess demand indicator for the U.S. is 11, and that nearly all the localities we looked at show excess demand for restaurants vs. the supply of potential restaurant workers. The localities currently facing the largest gaps between demand for restaurants and supply of restaurant workers are those local economies that rely strongly on tourism and the provision of leisure/hospitality services—places like Palm Springs, New Orleans, Las Vegas, Virginia Beach, and yes, even the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Economic activity in these places was practically shut down during the pandemic, and while the demand side of the economy has quickly gone back to full speed with many visitors now fully vaccinated (56 percent of the US adult population as of June 21 according to the CDC), the supply side of the economy—fundamentally constrained by the available workforce—is unable to go from zero to 60 so fast.

Several factors are constraining labor supply in these areas with high excess demand/shortage of restaurant workers:

- Ongoing suspension of “seasonal” work visas for foreign visitors. Normally the summer beach resort areas rely greatly on young adults visiting from abroad (especially Eastern European countries) on temporary J-1 cultural exchange visas. But these programs were shut down at the start of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 and are yet to be restarted. For example, according to State Department data, 2,353 Romanians were granted J-1s in April 2019, but only 11 in April 2021. The current workforce is constrained to mainly local residents, and it’s harder to attract seasonal help from other parts of the country when there are so many other jobs closer to/more convenient to younger workers where they live—and when many young people like the rest of us would (frankly) rather get out and experience life for a bit now that things are reopening, rather than immediately getting back to (or started with) work.

- Limited match-up of jobs to affordable and desirable housing/living arrangements for workers in these resort areas. With the pandemic completely shutting down business activities in these towns, any people who had previously lived in these towns to work (vs. for leisure) will have left last year. There’s not enough of a full-time resident, local labor force to draw from, and it’s not quick or easy to attract and physically relocate outsiders (but Americans) in. It is impractical to expect young workers to commute daily to the northern beaches of the OBX from other parts of NC or VA, yet it is nearly impossible to find an affordable place to rent for the summer. (A bartender I met in a Corolla, NC, restaurant told me that he shares a beach house with 17 other people. And a waiter at another restaurant told me he had left the area and his restaurant job last spring but came back this year when the restaurant owner was able to rent him an apartment unit above the restaurant.)

- The fundamental demographics of full-time residents in ‘leisure towns’ work against an ‘at the ready’ supply of restaurant workers. Palm Springs is a prime example of a demographically specialized place: predominately white, higher-income, and older (retiree) community (also for some reason, male-dominated)—people who like to consume services (like dining out), not work in those industries.

- Many prior workers in leisure/hospitality jobs have left the industry during the pandemic, switching industries and employers, or pulling out of the labor market entirely to care for family members. It’s not that simple to bring back these workers now that they’ve been out of the leisure/hospitality work for over a year. It’s not just a question of offering them higher wages. Leisure/hospitality workers are disproportionately young, female, people of color, and immigrants, and many choose these jobs for their part-time flexibility, despite lower wages and lack of benefits. But now leisure/hospitality jobs might no longer have the advantage they used to in terms of flexibility. And schools had not yet returned to fully in person, and now school’s out for summer! (The suspension of temporary visas for foreign visitors is also greatly constraining the market supply of caregivers.)

- Pace of demand restart simply too much to keep up with. Given how constrained Americans have been over the pandemic year in terms of getting out and spending money, we’re now witnessing the expected unleashing of what I call “cooped-up demand”—the most extreme version of “pent-up demand” we’ve ever seen! I sense we’re seeing somewhat of an overshooting of demand right now, and that we’ll see both demand settling down and supply catching up over the rest of this year as the initial novelty of the reopened economy fades.

In contrast, bigger cities or metro areas with more diverse, year-long resident populations are experiencing less of a shortage of restaurant workers; the cities we find have below-average indicators are Miami, Orlando, San Diego, Nashville, Austin, and DC. (DC is the only example of a place which registers a negative on our indicator measure, but DC is one place where it’s probably unreasonable to assume that even young people searching for “jobs near me” are truly open to working at restaurants.) While demand for restaurants is also picking up in those cities, the recent increase is not as dramatic given that economic activity in those places was never fully shut down by the pandemic, and the supply of potential workers never fully jumped those cities’ ships.

With the 4th of July holiday just around the corner, our “summer of freedom” (as President Biden has called it) will be in full swing. We will continue to see increases in leisure/hospitality consumer spending and businesses struggling to hire enough workers to fully meet their demand. Many businesses will respond by making those leisure/hospitality jobs more desirable (higher wages, more benefits, greater flexibility). We shouldn’t interpret the current excess demand for restaurants and other leisure/hospitality spending as a sign of an undesirable “overheating” of the entire economy, but rather as demonstration of the inevitable difficulty of quickly rebuilding and restarting a supply side of our economy that has not only been shut down for so long but has gotten smaller. (Remember, we’ve lost a lot of immigrant workers and working women—which were two of the fastest-growing segments of our U.S. workforce pre-pandemic.) The economic “recovery pains” we’re currently experiencing signal that the post-pandemic economy will likely be quite a bit different. To bring back the full potential of our economy will require giving more people more reason to participate—creating a truly more inclusive (and therefore more resilient) economy. And that’s a good thing.

More of my “Economist Mom” perspective on the economy to come this summer. Stay tuned!

Diane Lim is serving as an Economist Mom in Residence at Avison Young. She works closely with the firm’s insights team who drives AVANT by Avison Young, which leverages real-time data and analytics to make cities and location-based decisions more transparent and efficient. Diane looks at the data underlying issues related to the U.S. economy, recovery and our communities. Her views are her own. Based in Washington, D.C., Diane is a proud mom to four exceptional adults.